In 1831-32 the agitation about the Reform Bill and long continued opposition to it, had caused a great stagnation of business. Trade was dull; there were many failures; all were in difficulty, and many in distress.

A little before this time appeared Mr. Fergusson’s account of his first tour in the United States and Canada, and not long after it his second tour, while the Chambers were publishing their admirable papers on Emigration to America, containing letters from actual settlers in Canada. The eyes of thousands were turned to Canada, as a place of refuge.

Three friends in Aberdeen, afterwards joined by others, were in the habit of meeting frequently to consider seriously the advantages or disadvantages of emigrating; and at length, after obtaining all possible information, they resolved to go out, settle side by side, and thus form a little Aberdeen colony and give it the name Bon-accord — from the motto of the town’s arms.

TRIP TO CANADA 1834 by George Elmslie

All preparations having been completed, and abundant stores of clothing, etc., laid in, on the 30th of June, 1834, we set sail from Glasgow, in the Fania, Capt. Wright, Commander. The voyage was pleasant. We reached safely the banks of Newfoundland where we were becalmed two days.

Our passage up the St. Lawrence was very rough – the wind ahead and constant tacking. At length we reached Grosse Isle, the quarantine station, and were immediately boarded by the authorities. Here first we met with Mr. Watt and his party – a blythe sight – for I had known him in Aberdeenshire. On the second day we reached Quebec, the next morning set sail for Montreal, which we reached in two days more. From there, we proceeded up the river to Ottawa, and by the Rideau Canal to Kingston. We reached Kingston on the ninth day after leaving Bytown (Ottawa) and boarded the steamer for Toronto. On Sabbath, 14th August, a bright, beautiful day, we were walking its streets.

ELORA

At Elora, having taken lodging at the tavern, and got some refreshment, which we greatly needed, we enquired for Mr. Gilkison, (the late David Gilkison) and were told that he owned the large log house we had seen on entering the clearance, and kept a store there. We rested a while and then called there, when we learned that he was from home, but was expected to return next day.

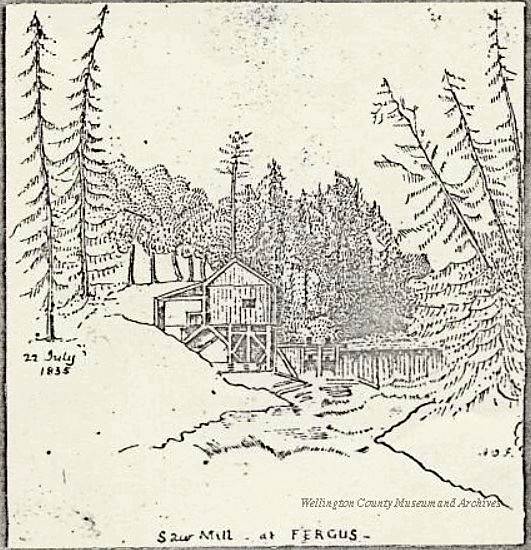

From the door of the store, we observed that a part of the opposite river bank was cleared, with a small shanty upon it – a saw mill – beneath which were “the Falls.” We also observed a bridge on a line with the store. We hastened down to the saw mill, which was not then working, being out of repair, and from beneath it got our first view of the Falls, which, notwithstanding our having so lately seen Niagara, appeared to us really magnificent and extremely picturesque. We then returned to our lodgings at Mr. Martin Martin’s. Next morning, finding that Mr. Gilkison had not returned, we resolved to visit Fergus.

FERGUS

We were shown the brush road, the only road leading to it, and on enquiring for Mr. Wilson, who had left Aberdeen some months before us, were told that his clearance was right on our way, and would be the most direct route to Fergus.

We soon got there, and found him in his logging habiliments – picturesque, withal, but certainly not white as snow. We spent an hour very agreeably, and greatly admired the romantic position of his cottage, perched on a projecting ledge of rock, commanding a view of the Grand River, with its steep rocky banks and lofty trees, for a long way up and down – nor less admiring the comfort and even elegance within, embellished with old country ornaments and some wild flowers of the forest. He led us through his chopping, where we first saw the process of logging, into the path to Fergus, near which we met Mr. Webster and two of Mr. Ferguson’s sons, in the light deshabille common in those days, carrying axes.

On mentioning our object, Mr. Webster said he would be at home in the evening, and would be glad to show us his maps and further our object in any way he could.

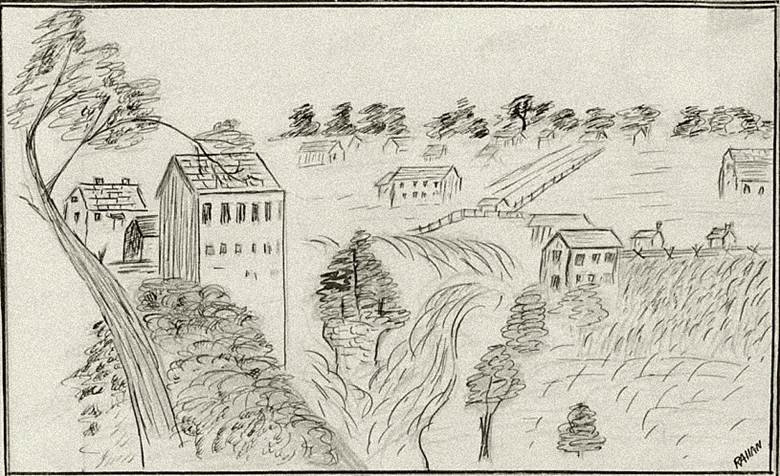

We were soon in Fergus, then consisting of a tavern, unfinished; a Smithee; two or three workmen’s shanties of the rudest kind; and Mr. Webster’s house, a neat log cottage with the best finished corners, roofing, and windows we had yet seen.

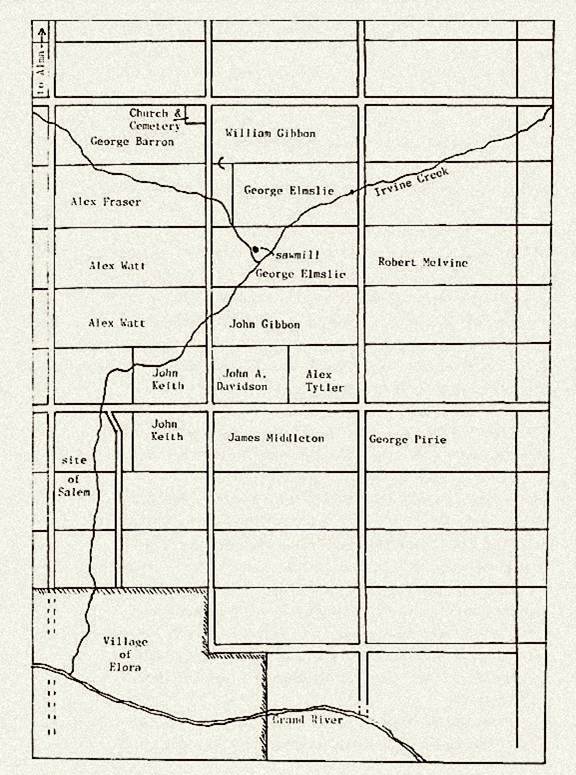

As a matter of course, we went to the tavern, where were workmen in every part of it, fitting up, planing, plastering and chinking. We sauntered about, seeing the little that was to be seen, looking at the dam, the falls, the black pool under the rude half-finished bridge, and the stumps wherever there was any clearance, which was mostly confined to the village site; and the banks of the river, which appeared to us much less majestic than at Elora – although the lofty, precipitous, water worn, rocky banks attracted much of our attention. We then went to Mr. Webster’s, and saw the plan of his lands, but found that all the choicest situations, all the lots nearest Fergus, all the lots bordering on the rivers and streams, were already sold; and he had not a block left of any extent nearer than four or five miles from Fergus. On pointing out this to Mr. Webster, he then advised us to examine Mr. Gilkison’s land that, as far as he knew, very few lots of his had been sold, and we would therefore have the pick of the block and many choice sites on the Irvine and other streams. We then took our leave.

When we entered the tavern in the evening, it was swarming like a hive with artisans, millwrights, and carpenters, together with several young men with capital, sons of Scotch proprietors – mostly intelligent young men from Perthshire, Dumfries, and the south of Scotland; and from all we received a cordial welcome in the genuine Scotch style and in hamely Scotch. On asking if we could be accommodated for the night, “I kenna what ye’ll ca’ accomodated; but ye’ll just get yer share o’ the flure – we’ll no can do mair for ye – an’ yer bite an’ yer sup wi’ the lave”.

The night was very joyous: The novelty of the situation – the rudeness of accommodation – the drollery of the make shifts – the mixed yet entirely Scotch character of the society — the hopes upspringing in the breasts of all— imparted a loveliness, a zest, and a joyousness to the conversation such as I have rarely experienced. The hackneyed lines, “The nicht drave on wi’ sangs an’ clatter, an’ aye the yill was growin’ better,” was not on that occasion a poetic fiction, but a literal fact, for, up to that evening I had small liking for ” this Canada.”

Part 4 – George Elmslie 1834

ELORA – IRVINE RIVER

We returned to Elora next morning, and found Mr. Gilkison, who showed us the map of his lands, pointing out how beautifully they were watered. We therefore resolved to spend the next two days in exploring a part, at least, of them.

I was now satisfied. We had found a block suitable in all respects for our projected colony. The quality of the soil, as indicated by the trees and their size, was equal to any we had seen; watered in such a manner as we had nowhere seen; the streams living, clear, rapid, and the chief of them on a limestone bed, and therefore healthy; the society was superior to what we could have anticipated – the newer settlers almost entirely Scotch, the older, around and in the neighbourhood of Elora, respectable, intelligent English men; the block bordering on the new and rapidly rising settlement of Fergus, with the immediate prospect of having a Church and Schools; the only drawback – far in the woods and the roads execrable.

BACK TO TORONTO

We therefore immediately called on Mr. Gilkison, to ascertain on what terms a block of 2,000 or 2,500 acres could be purchased. His reply was that he could make no reduction from four dollars per acre, but he referred us to his brother in Toronto, Mr. Archibald Gilkison, who was agent for the estate of his late father. It now only remained that we should hasten to Toronto, which hitherto had been our headquarters, and we set off next morning.

We lost no time in going to Mr. Gilkison and finishing the bargain. He would make no deduction in the price, four dollars per acre, but agreed to allow half a dollar of the price per acre to be expended within the block in cutting roads and making bridges.

Part 5 – George Elmslie 1834

TO BON ACCORD

Mr. Gibbon had engaged six waggons, including a light one for the ladies and children, and, it clearing up after dinner, the cavalcade started.

The morning was clear, with a heavy, white frost. We got to Guelph about one p. m., and proceeded about four miles to a crossway of the direst kind, half broken up, with a mud hole at the end which we tried in vain to avoid, but had no help but to plunge into it, and there the waggons stuck fast. The hole being of unknown depth, it was thought useless and even dangerous for the horses to employ the former expedient of doubling the teams.

Happily, there were two farm houses near, whither we sent for two ox teams, and by means of doubling them and prying with rails we got the waggons drawn without any serious breakage; the oxen drew on to Blyth’s – three young men from the west of Scotland who had recently settled there and built an inn. The house was just roofed, partly chinked, the window frames in, but unglazed, the doorway posted up, but without a door. Though the accommodation thus seemed somewhat unpromising we were glad to embrace it, for it would have been madness to have attempted going further by such a broken and wild track; the teamsters, therefore, in African phrase, untrekked.

We entered under the roof, for it was little more than a roof, only one side of the building being chinked, and the blazing log pile diffusing light and warmth soon melted the ice of ceremony. The young men expressing themselves greatly perplexed as to how they could accommodate us, the lassies volunteered to look after the cooking department, and the married ladies to the beds. They were thus set at their ease, and the joke and the laugh went round.

Our servant Elsy greatly amused them by the fun of her jokes and her smart repartees, and we were soon as merry and comfortable a company as persons who had never seen each other until half an hour before could be. To our supper was added the luxury of venison steaks; and the novelty and strangeness of our circumstances, together with the fatigue and roughness of the day, reconciled us even to the Canada punch. The beds of the principal members of the party were spread along the upper floor, and we slept very comfortably.

We left about ten o’clock next morning to accomplish the last stage of our journey, and reached Elora about three p.m., with less obstruction than we expected, our greatest difficulty being within a quarter of a mile of Elora.

Part 6 – George Elmslie 1834

ELORA AGAIN

Mr. Watt and his party got immediate possession of the shanty on the north side of the river; we taking lodgings in the tavern till a house, which had just been raised, should be made ready for us. And here I would gratefully record the courtesy, the kindness and attention shown us by the late David Gilkison, Esq. Warm hearted, intelligent, and having seen a good deal of the world, and with considerable knowledge and experience of Canada, his house and society were an agreeable refuge, and caused many an evening pass pleasantly which otherwise would have dragged heavily; when any of us needed assistance he was ever as ready to give as we to ask it. His father’s purchase here and his own exertion undoubtedly gave the first impulse to the settlement of this flourishing part of Canada West.

As was before mentioned, we took lodgings in the tavern till the house which was preparing for us should be ready for our reception. The landlord, Mr. Martin, and landlady, were exceedingly obliging and attentive, and we were as comfortable as one room, close to the bar room and serving the manifold purposes of dining-room, bed-room, drawing-room, kitchen and wash house occasionally, and, as it unhappily turned out, hospital also, could allow us to be.

The first thing now necessary to be done was to make a practicable road into our new possessions; it, of course, could only be at first a ‘brush’ road. The parties who were engaged in making this first road to Bon accord were Messrs. Watt, John Keith, myself, William Gibbon, John Fergusson, and Sam Trenholme: the last two were the Engineers and Pioneers. We started from Elora immediately after breakfast, and taking the line between the eleventh and twelfth concessions, by four o’clock in the afternoon completed a very good ‘brush’ road to the Irvine, making the ford a little above the present bridge.

Part 7 – George Elmslie 1834

CLEARING AND RAISING

We now set about clearing, and raising houses. Mr. Watt let thirty acres to be cleared and fenced, at about sixteen dollars an acre, to Messrs. Nicklin and Elkerton, together with cutting and hauling logs for his house. I let ten acres to be chopped at six dollars an acre; five to be cleared and fenced, and two or three acres, around the house to be cleared, but chopped close to the ground, at twenty dollars an acre. This job was taken by William and Richard Everett, and also the cutting and hauling of logs for the house, forty-two by thirty-six feet, for which I gave fifty dollars. The remainder was cleared by Mr. Letson.

Sometime about the beginning of November, Mrs. Elmslie, William Gibbon and I, went to select a site for our house. On the twentieth and twenty first of November it was raised. Nearly the whole of the then population of Nichol and Woolwich were there. All the first settlers in Nichol, the English settlers in Woolwich, a great many workmen from Fergus, the first settlers on the Upper Irvine, all our choppers, the carpenters from Elora and its immediate neighborhood, old King Reeves, being our waggoner, carrier, purveyor, etc. The first day the work went rather heavily from the extraordinary size and weight of the logs, so that when night fell, it was little more than half up. Nearly all agreed to see it finished on the morrow. Those who were nearest to the scene of action went home; but the night being mild and dry, a great many remained on the spot and, as there was plenty of viands and punch, they made a large fire, and passed the night very comfortably.

Next day all went to it with a hearty goodwill, and considerably before night, the last log was put up, amid tremendous cheering. As Mr. Watt’s raising was to be next day, Messrs. Nicklin and Elkerton invited those who were to stay over the night to the shelter of the shanty. The night being cloudy and dark, a great many stayed, so that the shanty was completely crowded; we had scarcely sitting room; and a scene of mirth and fun, and somewhat boisterous play, without brawling ensued, such as I have rarely seen here, even in those early days. It continued till near morning, for there was no sleeping room. Some, however, took shelter under the thick cedars and hemlocks, which were in abundance on the bank. At daylight it began to rain, which, by the middle of the forenoon, changed into a thick fall of snow, and continued throughout the day, making the work, though far easier than that of the former two days, much more cheerless and uncomfortable. An accident had like to have put an end to my further clearing the forest. The “cornermen” were vieing with each other who should lay his corner most quickly; the falling snow made the axe handles slippery, and the axe of one of them slipped and whizzed past my head with great velocity, almost grazing my cheek. This was one of the providential deliverances I have experienced during my life. The raising was finished early in the afternoon, and we went to our quarters cold and dripping.

DIVINE SERVICE

About this time, we formed a resolution to have – Divine Service on Sabbath, at least once in the day. Our first meeting for this purpose, was in the shanty occupied by Mr. Keith, and Mr. Watt, on the north bank of the river, at Elora. Shortly after, Mr. Gilkison invited us to his house, where were assembled the villagers, and a few of the nearest settlers. We had the usual exercises singing, praying, reading the Scriptures, and a sermon, some times of Blair’s, sometimes of Newton’s, sometimes of others. We continued this as long as we remained in the village.

MOVING IN

Towards the end of December, we got into our new lodgings – the building provided for us being now roofed and chinked, the doorway hung, and the windows in and glazed – things which did not always happen simultaneously in those days. Our beds were arranged in this wise: at about seven feet from the western gable a strong beam was fastened from side to side; this was divided into three compartments by white cotton screens; then boards were placed across, and on these were laid mattresses and beds. This was our common bedroom, partitioned off by a white sheet extending from side to side. Our cooking stove was placed towards the other end, and in the centre our common table, formed of the large chests; trunks and smaller boxes were our seats. Thus, situated we felt comparatively comfortable, only at times the hive was too small for the swarm.

On Christmas morn we were serenaded with Christmas carols, sweetly sung, and accompanied by the flute – a greatly more pleasant arousing than the tumultuous noise in a Scotch town.

The leader of the choir, we found, was Mr. Patmore, carpenter, an excellent singer and a good musician; and certainly, our absence from home for six months, and our position – a small spot, a lodge in a vast wilderness, a boundless continuity of shade – greatly enhanced the delight of the concert.

The winter, as we were informed, was unusually mild, the thermometer not often going below zero, and seldom as low as that; there was no very great depth of snow; there had been, moreover, a singularly long and beautiful Indian summer – the former part of it bright, sunny and deliciously warm; toward the close of it, the thick, smoky atmosphere, and the sun rising fiery red and continuing his march until night as if half eclipsed.

Leave a comment