The Valley of the Six Nations: A Collection of Documents on the first nations of the Grand River.

Edited by Charles M. Johnston

Published by The Champlain Society for the Government of Ontario

University of Toronto Press 1964

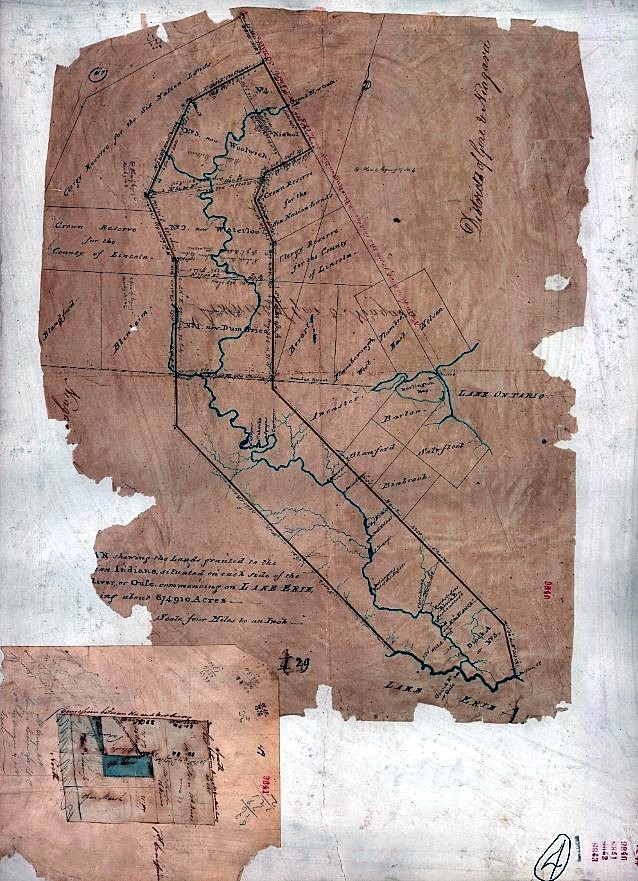

While the disputes continued about the precise meaning of the Haldimand proclamation, the Six Nations were establishing themselves on the Grand River. In November, 1784 they were promised government assistance for their settlement, and a mill, church, and school. During the winter and spring of 1784-5 they moved from Niagara to their new home. The Mohawks settled around Brant’s Ford; the other refugee Nations organized their communities to the southeast. Immediately adjacent to the Mohawk tract were those of the Onondagas and Tuscaroras, on the eastern and western banks of the river respectively. The latter nearest neighbours were the Senecas and the Oneidas who occupied corresponding locations, and the Cayugas who had taken up their allotted land near the mouth of the Grand. There were in addition, representatives of other tribes who had attached themselves to the Six Nations and accompanied them to the west after 1783, notably contingents of Delawares – the most numerous of these allies, Tutelos and Nanticoke.

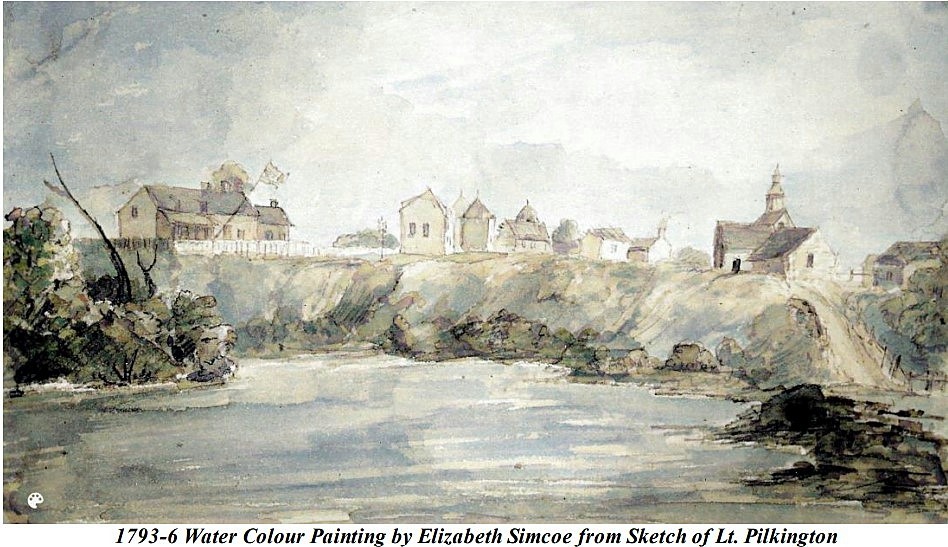

The Mohawk Village, Grand River 1793 from a sketch by Lieutenant Pilkington

Other Settlers

One of the major problems arising from the Haldimand grant was the question of whether or not first nations could dispose of their lands directly to whomsoever they chose. In the years immediately following the grant it was relatively easy for the strong-willed Brant to take the initiative and to invite white settlers to the tract, actually providing them with rough land titles. It appears that even before the area was formally transferred to the Six Nations, several whites, including two named Preston and Dodge, had taken up residence in the vicinity of present-day Galt and Kitchener, principally as fur traders. Subsequently, in 1787, a number of families, all friends or acquaintances of Brant – the Dochsteders, the Nelles, the Huffs and the Youngs were issued deeds by the chief clearly stipulating that their grants extend in length “three miles back from the river” were to “be possessed by their recipients and their posterity forever:” and it is worth noting, were “never to be transferred to any other”.

After the Youngs and their neighbours occupied their holdings, other friends of Brant, the families of John Smith and John Thomas, encouraged by the chief’s offer of land, made their homes in the neighbourhood of what came to be known as Brant’s Ford. Over the next quarter of a century, a considerable number of Europeans and Americans obtained similar leases authorizing them, at least so far as Brant was concerned, to occupy and improve lots overlooking the river. They included Benjamin Fairchild and Alexander Wesbrook, two “Volunteers” who had served under the chief during the American War of Independence and moved to the Valley in 1788; Isaac Whiting, who five years later leased “for 999 years” a farm on “Fairchild’s Creek” so called; Godin Chapin, Whiting’s son-in-law; David Phelps, who secured a lease in 1801; William Dennis, who settled in the Nelles Tract in 1806; Ezra Hawley, self-styled “son of a Loyalist”, who occupied a farm in 1811; and one Benaijah Mallory, who after obtaining a lease in 1805 and prospering as a farmer, had a most diversified career in the colony, acting occasionally as a spokesman for the Six Nations, serving as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada and still later defecting to the Americans during the war of 1812.

Augustus Jones [following information is from the Canadian Dictionary of Biography, not part of the Valley of the Six Nations]

Joseph Brant employed Augustus Jones on many surveys on the Grand River. The two men, who lived at opposite ends of Burlington Beach, became close friends. In addition to leasing him land on the Grand, Brant made Jones his agent on occasion, in land purchases among other matters, and named him one of his executors.

The ambitious Jones intended to build up large personal landholdings in Upper Canada. Through the system of petition and grant, he acquired extensive lands in Saltfleet and Barton townships during the 1790s, in addition to town lots in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) and York (Toronto). In 1797 and 1805 he received from the Mohawk war chief, Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*], reputedly in payment for surveys on the Grand River, two leases of land there which together comprised roughly ten square miles. Jones established family ties with both the Mohawks and the Mississaugas. On 27 April 1798 the surveyor, then in his early 40s, married Sarah Tekarihogen, 18-year-old daughter of a Mohawk chief. Eventually eight children were born to them. Simultaneously, at least in the early years of this marriage, Jones maintained a previous relationship with a young Mississauga woman, Tuhbenahneequay (Sarah Henry), the daughter of Wahbanosay, a Mississauga chief. Together they had at least two sons, Thayendanegea [John] born in 1798 and named after Brant, and Kahkewaquonaby [Peter] born in 1802.

portrait by George Romney 1776

The Valley of the Six Nations continued:

Governor Simcoe [1791-96] positively refused to permit the Six Nations to sell or lease any part of their reserve, not only because he regarded any such action as a violation of the orders governing the matter, but also for fear that they would promptly be taken in by unscrupulous “Land Jobbers”. Simcoe remained adamant on this point to the very end. Brant argued vainly that the Six Nations could no longer hope to survive on the hunt exclusively and that failing the speedy agricultural development of the tract, their only recourse was to sell portions of it in order to obtain some financial compensation.

Simcoe’s decision in 1795 to apply for leave did not disappoint those persons who, like Brant had come to despise his manner and envy his authority. Giving as his excuse’s general ill health and a slow fever, Simcoe left York bound for Britain on July 24, 1796. He was replaced by Peter Russell.

Follow this link [control/click] and you can enlarge the map to see very clearly.

On February 5, 1798, the chief presented himself before the authorities and, through the good offices of government, formally transferred the lands already assigned to their several purchasers. Of approximately 570,000 acres that constituted the original Haldimand grant, approximately 350,000 were disposed of in the several conveyances that were formally sanctioned early in 1798 and parcelled out in six large but unequal blocks.

Although Block 4, the northernmost, comprising a little over 28,000 acres was not sold at this time, “owing to some Circumstances which did not distinctly appear to the Land Board”, no difficulty was experienced in finding purchasers for the remainder.

Block 1 (94,035 acres) had been deeded as early as March, 1795, to Philip Stedmond, who for some years operated a ferry service at For Erie.

Block 2 (94,012 acres) to Richard Beasley, James Wilson and Jean Baptiste Rousseaux. The last-named, whose family had long been associated with the Indian Department, had constructed the first grist mill for the use of the Six Nations at the Mohawk Village.

Block 3 [part Pilkington Township] (86,078 acres) was transferred to William Wallace.

Daniel Erb and Benjamin Eby, accompanied by Augustus Jones, ventured in Block3 and were impressed at once with its possibilities. This parcel of land had originally been conveyed to William Wallace who turned out to be almost as improvident as the wretched Stedman; unable to honour the terms of his contract he had been forced to relinquish all but 7,000 acres of the Block.

In May, 1807, the Six Nations assigned them the remainder of the tract. Naming the principal rivers traversing their enlarged domain the Conestoga and the Canagagigue, the new owners lost little time in surveying and charting the property.

In September 1806, the Six Nations [Brant] confirmed a transfer of 15,000 acres at the northern end of the Block made by Wallace to Captain Robert Pilkington of the Royal Engineers.

Brant’s Speech to Claus, re Block 3, September 23, 1806:

That Block No. 3, William Wallace’s seems to be so situated that the Patent cannot issue until the Certificate if produced agreeably to the order of Council of 5 February 1798.

We disposed of that Township to William Wallace but finding himself incapable of completing his contract, we were induced to dispose of part of it in the following manner – 7,000 acres to William Wallace in consideration of monies hitherto paid by him, and for work and labour done to our Council House, and other buildings at the Mohawk Village – also 10,000 acres for a House, Lot and Park for Ann Claus, the elder sister of the Six Nations, and daughter to our old friend Wanighjage (Sir William Johnson) – also 5000 acres for a House and Lot for our Agent, Captain Brant.

Also 15,000 acres sold to Captain Pilkington of the Engineers, and secured to Us by our Trustees….

Block 4 or Block Nichol

The early career of the northernmost of the Indian lands, Block 4 or Block Nichol, is shrouded in obscurity, for in 1798 when it was formally put on the auction block no buyer came forward. In later years, however, Joshua Cozens claimed that he had bought it from Joseph Brant in the fall of 1796. Cozen’s agent, a Connecticut merchant call Samuel Clark, attempted to sell the land in England, even trying to interest Simcoe in the speculation. Failing in his mission, Clark pawned the deed in 1799 for 250 pounds with a London firm which shortly afterwards went bankrupt. Cozens spent the rest of his life trying to substantiate his claim to the land; as late as 1839 he was still sending memorials to the British government. Despite the fact that Lord Glenelg had finally decided the issue against him two years earlier. It was agreed that Cozens had probably had some speculative dealings with Brant, but was denied that these ventures were ever sanctioned by the government, a step necessary to validate all Indian land sales.

Meanwhile, Block 4 had been sold to Thomas Clark, a Niagara merchant, in 1806. Two years later Clark sold the southern section, which passed to the Reverend Robert Addison, the rector of St. Mark’s Church in the village of Niagara. Upon his death Mrs. Addison conveyed it to Captain William Gilkison. [Gilkison also bought the North West part of Nichol].

Block 5 (30,800 acres) and 6 (19,000 acres) were granted to William Jarvis and John Dochsteder respectively.

In 1798 Block 5 near the mouth of the Grand River on the east side, was sold to the Provincial Secretary, William Jarvis. Apparently in financial difficulties, Jarvis had by the late summer of 1806 already decided to surrender that property, requesting his lawyer to advise him as to the best means by which this could be achieved. Acting on the recommendations proffered, he presented himself before a session of the Executive Council on Sept 4, 1806, and initiated proceedings for “yielding” the land, with but one stipulation: that in return for the surrender he be compensated for the money he had already consigned to Brant and the Six Nations. Although he failed to receive as much financial consideration as he had sought – Jarvis nevertheless returned the Block to the Crown on April 28, 1807, thus opening the way for its resale to a bonafide purchaser. Thomas Douglas, Lord Selkirk sought asylums in several locations on this continent for impoverished Highlanders and uprooted Irish peasants.

The Six Nations of the Grand River unifies all Haudenosaunee peoples under the Great Tree of Peace.

Today, the Six Nations is demographically the largest First Nations reserve in Canada. It is the only reserve in North America that has representatives of all six Haudenosaunee nations living together. These nations are the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, Tuscarora, and some Lenape (also known as Delaware) live in the territory as well. The acreage at present covers some 46,000 acres near the city of Brantford, Ontario. This represents approximately 5% of the original 950,000 acres of land granted to the Six Nations by the 1784 Haldimand Proclamation.

Leave a comment